November 28, 2017

"Safety Bob" Emery’s job is to make sure that the 17,000 people who work and study at UTHealth in Houston go home every day as safe and as healthy as they arrived.

By Daniel Oppenheimer

Every weekday at The University of Texas Health Science Center (UTHealth) in Houston, some 17,000 people come into work or class. That number includes students, technicians, doctors, nurses, waste management workers, administrative assistants, lawyers, and dozens of other types of workers. Dr. Bob Emery’s job is to make sure that those 17,000 people go home as safe and as healthy as they arrived.

"Safety Bob," as he's known around campus, is Vice President of Safety, Health, Environment & Risk Management (SHERM). In that role, he is responsible for environmental health and safety, employee health, and risk management at UTHealth, which has its main campus in Houston and five regional campuses across the state. This includes making sure that new employees are fully immunized, overseeing the people and processes that deal with chemical and radioactive waste, making sure that fire drills are regularly run in every building on the school’s grounds, and managing dozens of other procedures, drills, projects, and initiatives that deal with employee health and safety.

“My day is a good day when nothing happens,” says Emery, who is also a professor of occupational health at UTHealth School of Public Health.

In addition to all this, Emery is an evangelist among his colleagues, nationally and internationally, for systematizing and universalizing how institutions label, track, and measure their environmental safety and occupational health efforts. A common set of practices, he believes, would vastly improve the field’s capacity to learn from the successes and failures of each other.

“Comparison is the mother of insight,” he says.

Texas Health Journal recently spoke to Emery, who has been at UTHealth for 25 years, about his work.

Daniel Oppenheimer: In 100 words or less, why is what you do important?

Bob Emery: 2.1 Texans per day get up to go to work and do not come home. Because they die at the workplace. 1,005 Texans per day are injured at work. Many more get ill. At the national level, 16 people a day get up and go to work and don’t come home. This is why it’s important to be looking at occupational health and safety. People should be able to come to their workplaces every day with the expectation that they will free of reasonable risk of harm.

Good answer. What are some of the major reasons people die or get injured or sick at work?

A ubiquitous hazard for all UT campuses is fire. Virtually anyone who possesses a structure has a risk of a fire. At UTHealth we handle chemicals associated with research activities; some of those chemicals can be potienitally harmful. Because we exist to treat and prevent disease, we have labs that handle infectious agents. We have to make sure those are handled properly. There are radioactive materials that are used as tracers, so we have to handle those safely. We have to transport things, and driving is always risky. Those are just a few examples.

How is UTHealth doing, relative to other workplaces, on health and safety measures?

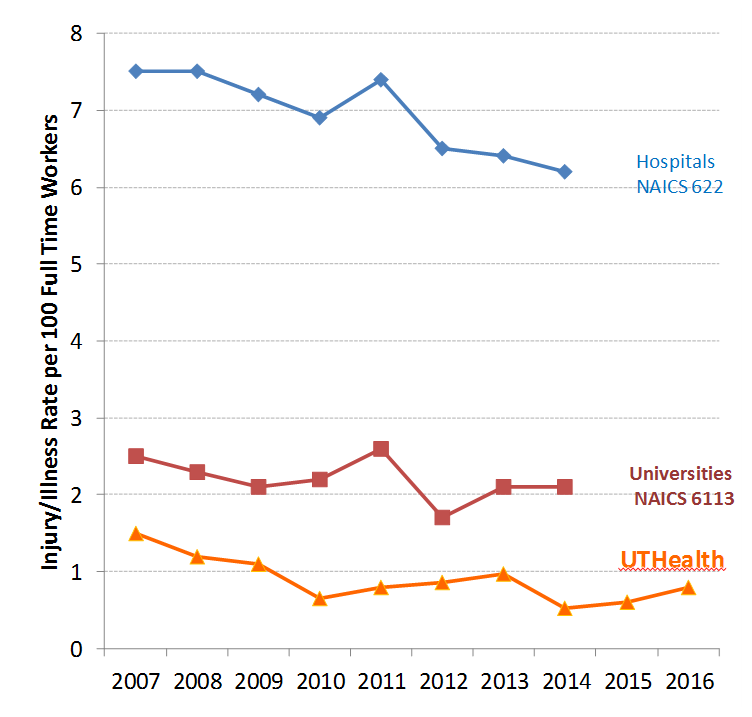

Annual Reported Injury/Illness Rates

We are doing well. Every company in the U.S. that employs 11 or more people has to submit data on injuries and illnesses to the federal government. If you look at our numbers compared to other hospitals and universities, you’ll see that our numbers are substantially lower than the national averages for both types of institutions. In fact, if you compare us to the recognized best in class companies, like DuPont and Dow, we are right in there among the best. You’ll also see a general downward trend over time, in injuries and illnesses, which is what you want to see.

I’m looking at that graph you sent me, tracking what insurance companies are charging UT health institutions for workers’ compensation polices over the last 15 or so years, and there is a dramatic drop across the board from 2003 to 2008. What happened? What did we start doing better that led to lower premiums?

Workers’ Compensation Insurance Premium Experience Modifier for UT System Health Institutions Fiscal Years 03 to 16

The big thing was recognizing that having occupational health nurses and case managers on site, rather than referring people out, could reduce the frequency of injuries, and also get people back to work sooner. It drove costs way, way down. Just to give you an example of the kind of thing we got much better at, imagine an animal care worker who hurts her back moving a large bag of feed. She reports to employee health, gets care on site, and also has a case manager who is able to assign her to restrictive duty, where she isn’t required to carry anything heavy, until she is back to full health. The sooner you get people back to work, even doing something modified, the better the outcomes, in all industries. And all parties benefit. Most people want to get back to work as soon as possible, and of course they want to get healthy faster.

How do you break down, internally, the types of activities your division does to keep everyone safe and healthy, and the quality of your performance?

We have four Key Performance Indicators.

1. Losses: This has to do with how many people are hurt and how much property was damaged. We want these numbers to be as low as possible.

2. Compliance: We get about 16 different inspections every year from outside agencies. So we look at the results of those inspections, and we make plans to fix what needs to be fixed going forward. We also do a whole host of internal inspections, all the time, to improve our performance and to correct or catch anything before the external agencies arrive.

3. Finances: We measure how much we cost to UTHealth, and what we’re doing to either bring in revenue or avoid costs.

4. Client satisfaction: How do our clients perceive the services we are providing and how open and accessible we are? Because a successful program necessarily depends on communication.

I’m curious about what cost avoidance involves, in your line of work?

Take hazardous waste. We do things that generate hazardous waste. That’s just part of the job. The most linear response to that is to hire someone to come and pick it up and dispose of it elsewhere, and that’s what a lot of places do. But that’s expensive, and often there are other options. If it’s an acid, for instance, you can sometimes mix it with other chemicals to render it non-hazardous. Then disposal costs less money. If a faculty member is leaving, and shutting down their lab, we can facilitate to see if other researchers can use their chemicals. With some radioactive material you can hold it, in a safe context, and let it decay away until it is no longer radioactive. If we’re smart, we can often save money, reduce environmental harm, and actually lower the overall safety risks, since it’s always better to avoid transporting hazardous material if possible.

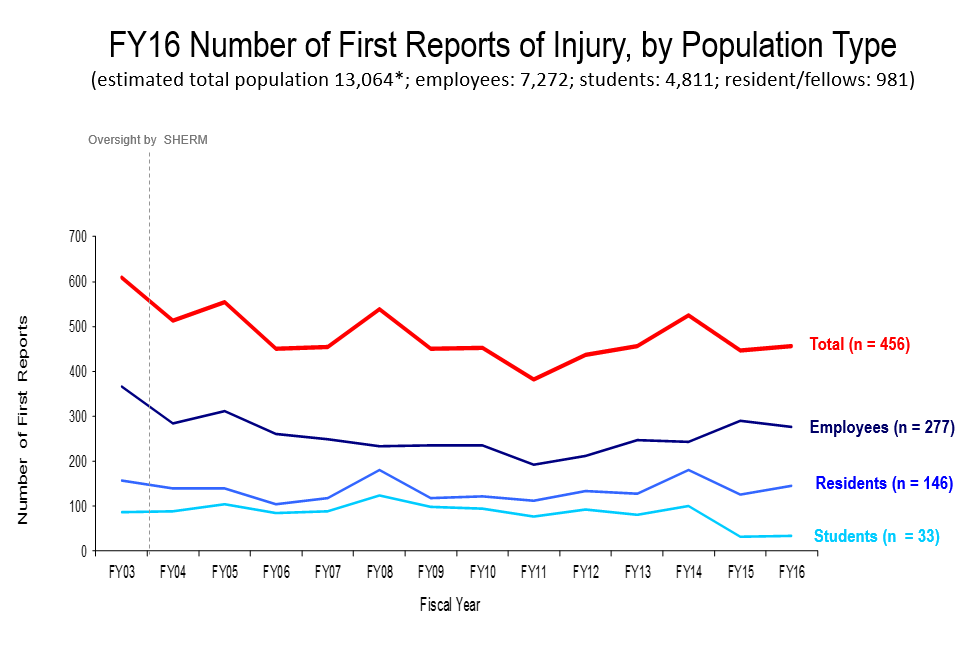

What happened in 2014? I’m looking at the injury trends from your presentation, and there was a spike that year. What went wrong? What did you do to bring the numbers back down?

You have to be careful, when you’re looking at aggregate numbers, that you don’t over-generalize. There is rarely one cause for an uptick, and therefore won’t be one intervention that is applicable across the board. The simple answer for 2014 is that most of those injuries came from dental students, who have to make rubbery dental devices that are carved by hand. These students were cutting themselves with these razors that were being used for the carving. There were also some medical students hurting themselves while suturing. As we sense trends emerging, we drill in, move in, and reverse the trends. So we addressed those specific contexts, and were able to reduce injuries the following year.

Let’s go to the bigger picture. What are some of the global problems you’re hoping to help solve?

Comparison, as they say, is the mother of insight. A big problem we have right now, in our field, is that there are a lot of comparisons we simply can’t make because we’re not all tracking the same things in the same way. We don’t have the benchmarks.

We have been working with a team of public health graduate students to collect data from 150 colleges and universities around the country on the resources they devote to health and safety. What we have found is that statistically the only predictor for the number of health and safety workers an institution will have is the total amount of square footage. That is a simple finding, but a very powerful one. Now we can speak in units of square footage for what it takes to do safety. I can tell right away what it is going to cost, for instance, to do safety for a new construction.

But wait. You’re not saying that simply the number of people, or the money spent, determines how safe a space is, are you? That doesn’t sound right.

You’re absolutely right, and in fact I get that response from colleagues at other institutions all the time. What I say to them is that we have to lay down some benchmarks in order to even look at outcomes usefully. In order to properly identify peer institutions, and make meaningful comparisons about outcomes, we need to know about the square footage, the budgets, the types of activities, and so on.

Think about it like this. When you go to the doctor, you go in, strip down, and put on the stupid paper gown. Then the first thing they do, after saying hello, is pull up your electronic health record and look at an agreed upon set of health status indicators. Height, weight, BMI, blood pressure, etc. These benchmark indicators are what enable the health profession to do meaningful analyses of different treatment regimens, for example. But in occupational health and environmental safety we don’t have these consistent vital parameters. If we could, as a profession, reach consensus on what these indicators are, we could make comparisons. Then we could really start to unpack what works and doesn’t work. We’re getting there, and hopefully that will be my legacy. On my tombstone it is going to say ‘square footage.’

Where do you think some of the most important advances, in worker safety, are going to come? I realize you don’t have the data you want, but if you had to make an educated guess, based on your expertise and experience?

The CDC uses the term “winnable battles.” We always have many health issues that face us, but if you’re talking about winnable battles, I think where the greatest bang for the buck is going to come is in using design to reduce or eliminate risks.

If you have ever done home construction, for instance, you know that the default size of a sheet of plywood which is 4x8, is pretty heavy and unwieldy. If we redesigned it so that the standard was 4x4, we could probably reduce injuries. Roofing shingles come in a 60 lb. bag. Why do we package them that way? That’s a really heavy bag for people working on a roof to be handling.

There are enormous potential safety gains that could come from looking at where and when injuries are occurring, stepping back, and evaluating whether we can design out many of these risks. Think about retractable syringes, which are becoming more popular. Needlesticks are a major source of injury in healthcare settings. These retractable syringes are new devices where the needle automatically retracts after you give the shot. I believe a lot of the major improvements will come from things like that, which will come from bringing together design folks and health and safety folks to ask the right questions about how we can rework things.

There is always going to be risk. That’s just part of being alive. But we can do better.