Concussions in youth sports are common––we think. Dr. Munro Cullum is partnering with the UIL to try to track every sport-related concussion in Texas schools, and then figure out how to prevent them

By Kathryn Lundstrom

Population Health Scholar

University of Texas System

MA Student in Journalism

UT Austin Moody College of Communication

Trying a new tumbling pass as a 13-year-old gymnast, I over-rotated on the spring floor. Twisting through the air, all my focus was on keeping my body tight while spinning, until—SMACK.

I’d missed my feet and landed on my back, head coming down hard as I hit the mat. The room was fuzzy and spinning slightly, but I got up and embarrassedly told my coaches I was okay before getting back in line.

After my bad landing, moving through the gym felt like moving through a dream. Though my body remembered how to flip and tumble, when I looked at the clock I knew something wasn’t right. I couldn’t make sense of it, couldn’t quite remember what it was supposed to mean. It started to scare me—what was I supposed to be understanding?

Eventually the gymnasium solidified and my ability to read the clocks returned. But when I told my mother what had happened, she was horrified. If that ever happens again, she said, you have to stop practice, immediately.

“That was probably a concussion,” Dr. Munro Cullum, a clinical neurophysiologist, said when I told him the story. “That would be consistent, kind of that dreamlike state––I’m still functioning fine, but something’s off––and then it went away. The good news is that you recovered fine.”

For me, it was just a dizzy spell, but the long-term risks of repeated and undiagnosed concussions are largely unknown. Anxiety surrounding the dangers of concussions has been increasing in recent years as reports have surfaced regarding the dangers of football and chronic traumatic encephalopathy, the degenerative brain disease that’s thought to be caused by repeated blows to the head.

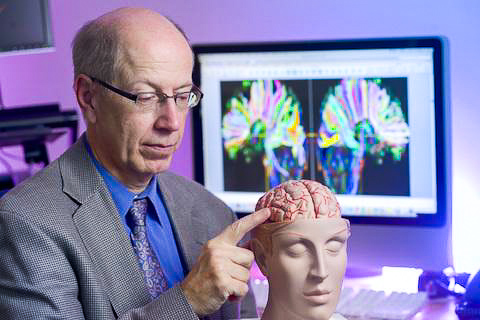

Cullum, who directs the neuropsychology program at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, studies brain injuries in youth athletes and is working to improve concussion tracking methods in the state.

When I hit my head, no one recognized it was a concussion––concussions just weren’t on our radar in the early 2000s. But since then, things have changed: Between 2001 and 2012, the rate of youth athletes headed to the emergency room for concussions doubled, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

There are a few caveats to the CDC data, however. As Cullum points out, tracking emergency room visits alone means a lot of concussions are likely flying under the radar. “There are some that aren’t being diagnosed, there are some that just go to the local family practitioner or other health care providers. Some only see the trainer,” said Cullum.

The general estimate, based on the CDC data, is that around 10 percent of youth athletes get concussions each year. And with around 800,000 kids playing sports in Texas, even that is a big number. “Yours is a really common story,” Cullum told me. The question is: What does that mean for kids? And how do we prevent more concussions?

But those are hard questions to answer without more information; we don’t even know how many concussions kids are getting, or which sports pose the greatest risk. Without a system for tracking concussions in youth sports, it’s hard to know where to start with intervention or prevention programs, or how to measure their success once they’ve begun.

It's that first step—better tracking—that Cullum and his team are working to tackle. In Texas, Cullum has created a registry, called ConTex, to track concussions in middle and high school athletes. In coordination with the University Interscholastic League, Texas’ school sports oversight body, Cullum’s research will include as many schools as possible so they can see the trends in youth sports-related concussions. “Our number one and two causes of concussion are football and soccer, but we’ve even got injuries from dodgeball, boxing, weight-lifting, la crosse, gymnastics and cheerleading,” he said. “We even have one tennis injury. Concussions can occur anytime, anywhere.”

The program uses an interactive smartphone app that trainers at schools can use to record when an athlete has symptoms of a concussion. “Concussions can be difficult to diagnose,” said Cullum. By using the app, developed by Austin-based Medical Innovation Labs, it’s easy for trainers to record—and recognize —those symptoms quickly and consistently.

Once the data is collected, Cullum said, the team can start analyzing it in the hopes of understanding where the risks are highest and which prevention techniques are working. But at this point they’re still in the “start up phase.”

“It’s just a matter of getting the word out to all the schools that this program exists,” said Cullum. “Having the superintendents encourage their people to participate.”

And if the UIL mandates the concussion injury reporting, which there’s been talk of, Cullum’s team would get full participation from Texas middle and high schools. That will likely be decided this summer, and would be a significant step forward for the team's research.

“First of all, we need to get a handle on how many concussions are occurring, where they are occurring, what sports, what age, etcetera,” said Cullum. “Are these statistics consistent with national metrics? What are the effects of age and gender?” By including all these factors and also assessing the kinds of treatment that the kids are getting, Cullum’s team hopes to get a better sense of where the risks are, what treatment works best, and which interventions are successful. “We know that some rest is good, but too much rest may actually be bad––may actually result in prolonged recovery times.”

And by gathering data from all around the state, Cullum’s team will be able to track regional trends as well. “We want to learn about which parts of the state have more concussions per number of athletes and what sports are they occurring in,” said Cullum. “We hope to identify those factors first, then look at recovery rates in those different areas.”

After that, Cullum’s team of researchers will work with the UIL to suggest equipment or procedural changes based on the findings. “For example, if the Panhandle has a very rapid return-to-learn, return-to-play time, we’ll set up questionnaires and interviews to find out what are they doing that’s working so well,” said Cullum.

Looking further ahead, Cullum wants to develop studies beyond middle and high school sports. He's had preliminary discussions with UT System about studying the campuses’ collegiate sports. Cullum’s also interested in comparing the rates of concussions between high school and club sports, like the program where I did gymnastics.

And while understanding the numbers is important for measuring the effectiveness of interventions, Cullum also wants to understand better the long-term effects of concussions. While working on the registry, Cullum’s team is recruiting current subjects to long-term studies that will assess the effects of concussions over time. They’re working, too, on a large study of NFL players to understand connections between a history of concussions and symptoms later in life.

Cullum worries that some of the fear of concussions in sport is getting overblown. “We really don’t want to bubble wrap our kids,” he said. “We want to let them experience life, and I think the advantages of sport far outweigh the risks.” To worried parents, he recommends that they find sports teams that are well equipped to handle injuries when they happen, but to understand that some of that is just part of life.

There’s a story that Cullum tells about a mother of two daughters––both in a competitive soccer club––who had repeated concussions. She started urging them to quit, and was delighted when one of them did and joined debate team instead. She was good at it, and the debate team was successful. At one of their competitions, the girls’ team was waiting to compete when the boys’ team came running in after a successful round. “This one boy’s flailing, he’s jumping around the room, and he nails this young gal in the temple with his elbow,” said Cullum. “She was knocked out for her worst concussion ever, during debate.”

His point is that while the data is necessary to develop safety procedures and improve techniques, sometimes concussions just happen. When I asked him whether concussions are inevitably part of sports, he responded: “It’s actually not even just sports––it’s life.”

But gathering and analyzing data allows the kind of tangible progress that the NFL has implemented, such as moving the kickoff line and penalizing the most dangerous hits. “There are certainly things that can be done,” said Cullum. Having the data is the first step to prevention––and Cullum’s team is in it for every step of the process.