The Texas Institute for Child & Family Wellbeing at UT Austin leverages their experience as researchers and social work practitioners to evaluate Project HOPES.

By Susan Kirtz, MPH

Managing Editor, Texas Health Journal

Director of Special Projects, Center for Health Communication

The University of Texas at Austin

63,657 Texas children experienced abuse or neglect in 2017, according to the number of confirmed investigations by Child Protective Services (CPS) at the Texas Department of Family and Protective Services (DFPS). That’s 8.5 out of every 1,000 children. Texas is taking steps to address this issue in our communities, and the Texas Institute for Child & Family Wellbeing (TXICFW) at The University of Texas at Austin plays a critical role in evaluating one of these initiatives.

In 2014, TXICFW received a contract to evaluate the effectiveness of Healthy Outcomes through Prevention and Early Support (Project HOPES), a community-based child abuse and neglect prevention initiative funded by the Prevention and Early Intervention Division of DFPS. Project HOPES awards grants to 22 implementing agencies serving 31 Texas counties that were determined to be high risk areas for child abuse and neglect. The initiative aims to empower local communities to collaborate to prevent child abuse and neglect through education, skill development, and capacity building.

Dr. Monica Faulkner

“What’s exciting about this project,” said Dr. Monica Faulkner, Director of TXICFW and Research Associate Professor at the Steve Hicks School of Social Work said, “is that DFPS really gave freedom to communities to identify what’s impacting child abuse and neglect in their areas and develop programming that’s related to their local context.”

At the core of Project HOPES are a range of evidence-based parent education programs. Sites also have the opportunity to leverage community resources to support local families, including novel interventions such as equine assisted psychotherapy in Amarillo and engaging refugee populations. Each individual site determines how best to recruit families experiencing risk factors, through methods such as screening in pediatric primary care clinics, recruitment at community-wide family events, and referrals through CPS.

Dr. Beth Gerlach

“Part of the push of HOPES is making sure that we’re identifying families that are really at risk for child abuse and neglect, meeting them before it happens, and wrapping their whole family in support,” said Dr. Beth Gerlach, TXICFW Associate Director.

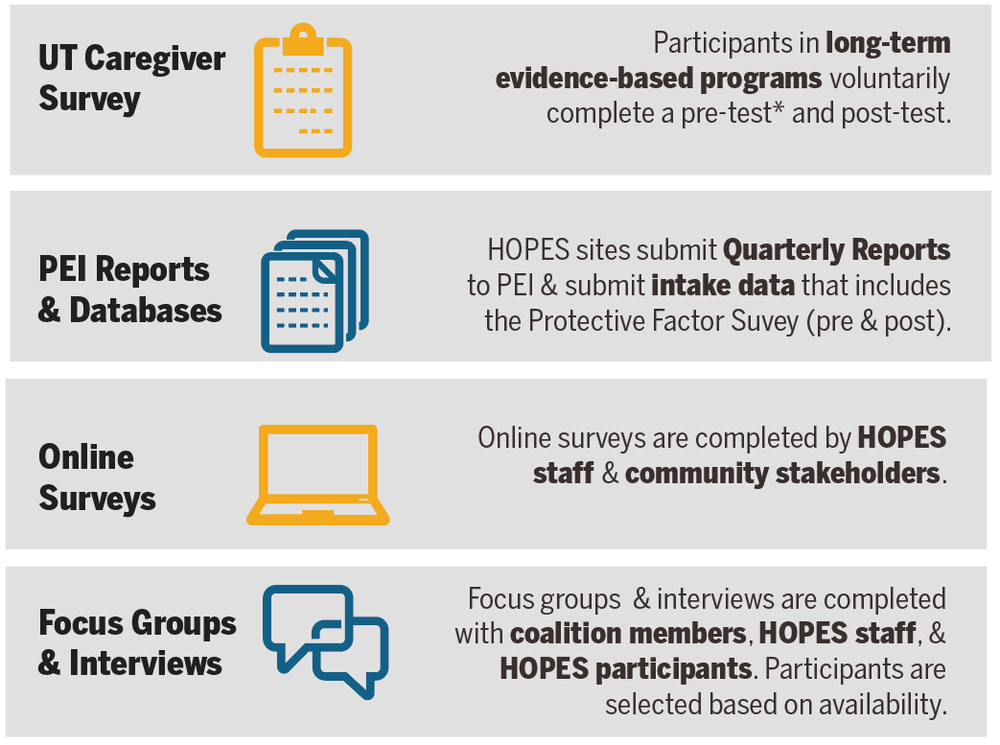

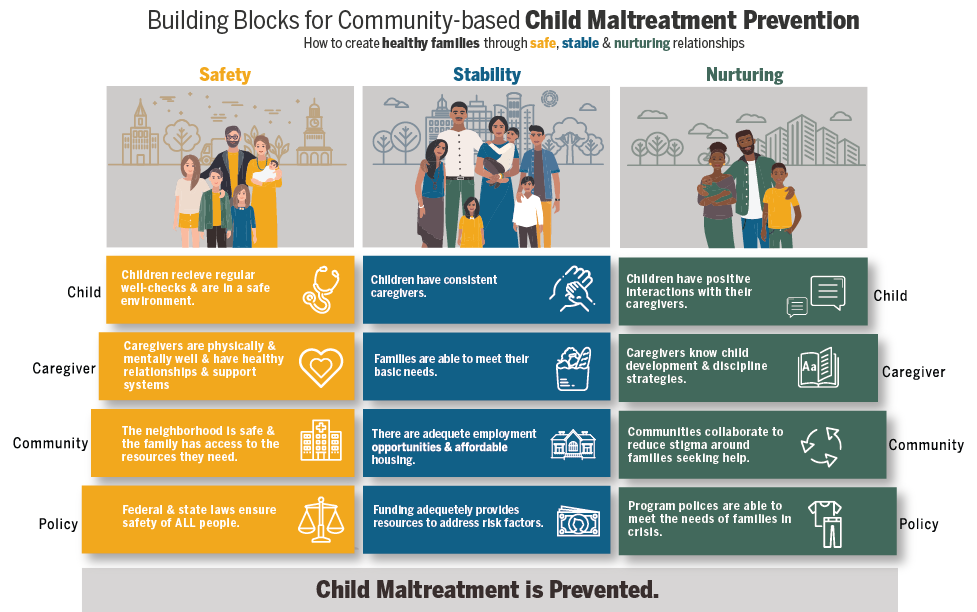

With 22 communities across the state implementing tailored interventions, Project HOPES is a difficult program to evaluate. In response, TXICFW developed a comprehensive mixed-methods evaluation plan including a literature review, secondary research on child maltreatment prevention, training materials, technical assistance, and data collection in partnership with each Project HOPES site. The team looks across the spectrum to identify successes and areas for improvement, including data collected through family, agency and community surveys, interviews and focus groups, along with data from DFPS. TXICFW also created a customized survey for families to identify safety, stability, and nurturing, complete with an instructional video on how to administer the survey, narrated by Gerlach.

As social workers themselves, the TXICFW team brings a unique perspective to program evaluation.

“The child welfare system is complex,” explained Gerlach. “Having social work practice and research experiences gives us both an insider and outside perspective that’s really important to interpreting and understanding the results that we’re seeing.”

Dr. Faulkner added, “Beth and I have worked with foster youth on the ground and we have a team of PhD researchers who also have that experience. You really don’t know a system until you’re in the middle of it. And you don’t know what the life of a family is like until you’re side by side with the family. I think that’s what distinguishes us as an institute.”

The team at TXICFW have a deep understanding of the individual and community-level risk factors that contribute to child abuse and neglect, including parental substance use, parental mental health issues, family violence, and multigenerational trauma - what they call “The Big 4.”

The team has done extensive work to provide evidence of these risk factors and make recommendations to the implementing agencies to improve and expand their programs.

“We know all of these factors can lead to child maltreatment, but no one was asking about it. And because no one was asking, no one was addressing it,” said Faulkner.

For example, research shows that adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) experienced by parents have a significant impact on their own parenting later in life. However, the TXICFW team encountered some resistance from sites asked to collect sensitive ACEs data from parents. To address this missed opportunity, Faulkner and her team used their practice experience to develop a training to help more than 1,000 social workers around the state communicate with parents about their own history of trauma. The training empowers workers to address multi-generational transmission of trauma, have a compassionate conversation to help remove shame, and help parents understand why it’s important to choose a more protected path for their own children than what they experienced.

“We discovered that families are pretty comfortable talking about their own experiences. The discomfort lies more with the worker who may be nervous and isn’t sure what to say,” said Gerlach. “Sites have started to recognize that, if they’re going to prevent child maltreatment, they need to find ways to address some of these issues in addition to providing parenting knowledge and support. That’s been an exciting change to see in the course of evaluating the HOPES program.”

Although the levels and success of data collection can vary by site, the team at TXICFW are dedicated to working collaboratively with Project HOPES communities to build buy-in and ensure that their evaluation directly benefits the program. The team stressed the importance of carefully explaining why they are collecting data and why it matters, allowing each site to understand how their services are making a difference for families. “We think it’s important to close that loop. We’re asking them to give us so much time and information that we want to be sure that we’re providing useful information back to the sites,” Gerlach said.

Swetha Nulu

Swetha Nulu, the Research Coordinator overseeing the Project HOPES evaluation, works collaboratively with each site to create a range of materials, including brief reports and infographics, to describe and visualize evaluation findings. The sites use these materials for their own grant-writing purposes and to communicate their successes with policymakers.

“What I really enjoy about working here is the insight of not just being the outside evaluator, but having a relationship with the different agencies,” Nulu said. “There’s a way to bring data back to them in an impactful way, while also being understanding and not just collecting surveys to collect surveys.”

Anyone who has worked in public health will tell you that measuring prevention is a lengthy and difficult endeavour. Long term outcome measures for Project HOPES include the number of children who enter foster care and substantiated maltreatment cases. Improvements may be masked, however, because increased awareness in a community may lead to increased rates of reporting of child abuse and neglect. Faulkner acknowledges the complexities,

“The community-based child maltreatment approach is still very new in Texas,” she said. “It appears to be on the right track, but the longer-term outcomes are going to take some time. It’s still worth the investment, and that’s what the results of our evaluation support.”

After traveling around the state to conduct qualitative interviews, Dr. Faulkner observed, “You can go from Laredo to Longview and you realize the families are very different, but the similarities in their struggles are there. No matter where you are, if you’re a parent, you’re going to struggle. We can all do a better job of supporting each other.”

Graphics for this story provided by Katelyn McKerlie, Communications Coordinator at the Texas Institute for Child & Family Wellbeing.